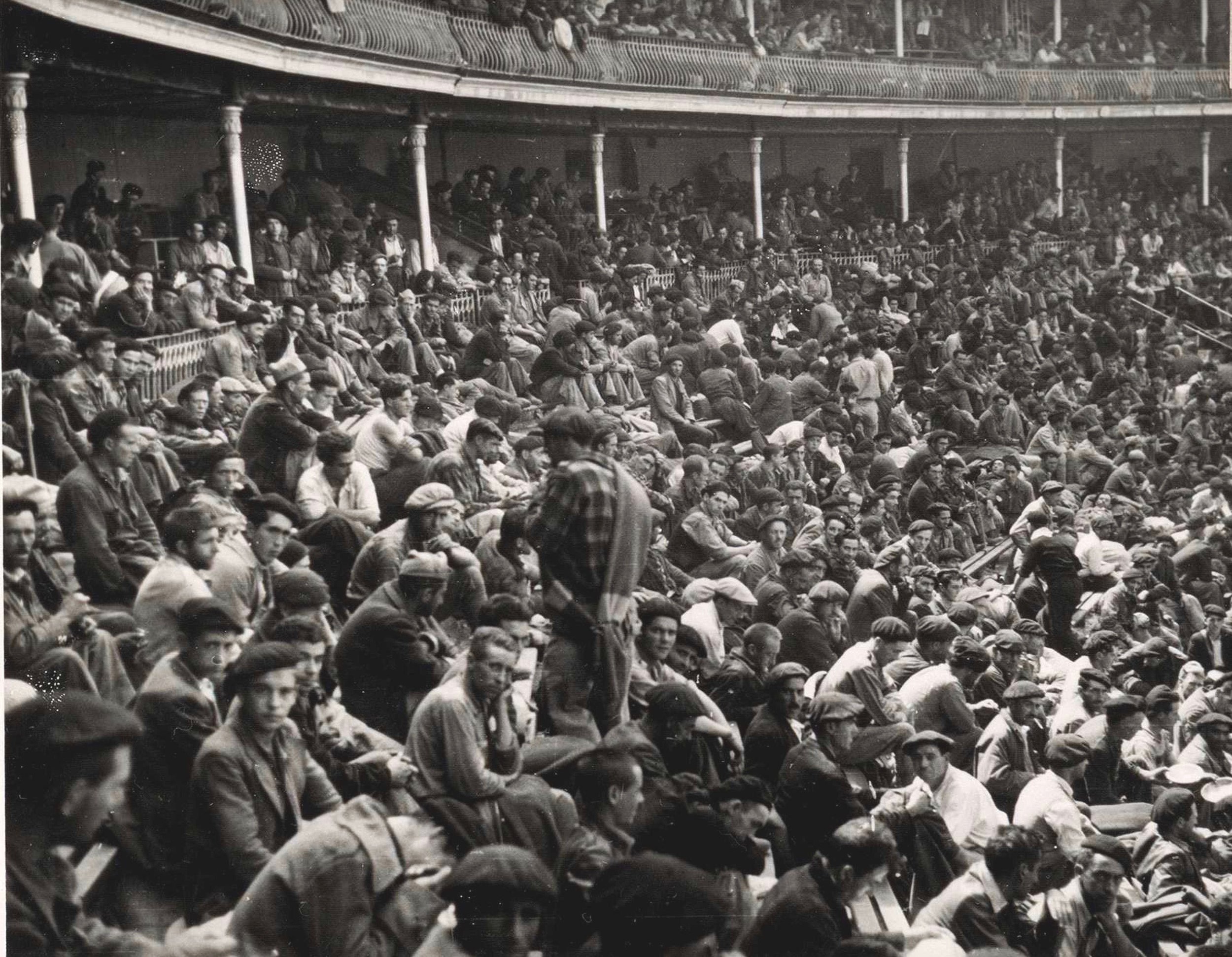

Remembering how bullrings were used in Spain’s Civil War

Santander’s bullring packed with prisoners after the city was taken by Italian and Nationalist forces

A row has recently broken out in Cáceres over plans to erect a monument outside the city’s historic bullring that was originally intended to commemorate the building’s use as a concentration camp by the Nationalist army during Spain’s Civil War. Having received funding for the monument from Extremadura’s regional authorities, the Partido Popular-led ayuntamiento has said the dedication on the monument will be in respect of “people who fought for freedom and democracy (1926-1975)” - an announcement that has angered La Asociación Memorial en el Cementerio de Cáceres, which regards the proposed inscription as being too broad and wants the original ring-focused intention carried out.

By my reckoning, at least 30 bullrings were used to contain prisoners, primarily by the Nationalists, during the Civil War or in the early months of the severe repression Franco’s victory led on to. In most cases, they were used as initial assessment centres. Each prisoner was classified as belonging to one of four groups:

A) ‘Afectos’ - people who were found to support the new fascist regime.

B) ‘Desafectos leves’ - people who may have volunteered for the Republican cause, but who had had no political role.

C) ‘Desafectos graves’ - officers in the Republican army, members of organisations sympathetic to the Republic, “enemigos de la patria”, etc.

D) People responsible for supposed crimes.

If you were deemed to be in A, you were either let go or forcibly conscripted into the Nationalist army; in B, you would be sent to a prison camp and be used as forced labour; while in C or D, you would either be given a long prison sentence or be executed. The Nationalists’ repressive net was cast wide to include not just those who had fought for the Republican side but also civilians deemed to have been supportive of Spain’s democratically-elected Republican Government.

1936

Bullrings that were used for assessment by the Nationalists from virtually the start of the war include Córdoba’s old Plaza de los Tejares and Granada’s former Plaza de Triunfo (the latter also served as a barracks), San Sebastián’s ‘El Chofre’, the old bullrings at Miranda del Ebro, Sigüenza, A Coruña and Carabanchel, and the current bullrings of Valladolid, Zaragoza and Talavera de la Reina.

Badajoz’s bullring after the massacre. At this stage, it appears that a couple of bodies (ringed) remain. The figure in the foreground is a Nationalist soldier.

Some bullrings gained further notoriety as the scene of executions. The most infamous was that of Badajoz, where, on August 14 1936, Nationalist forces under General Yagüe herded hundreds of people into the bullring, set up machine-guns and shot the prisoners in batches of twenty, their bodies taken by lorry to the town’s cemetery, where they were burned and then deposited in mass graves. Eight hundred people were shot that day and another 1,200 brought into the bullring that evening, the shootings beginning again the following morning, some of them witnessed by spectators sympathetic to the Nationalist cause. Most estimates put the numbers of dead at between 2,000 and 4,000 by the time the troops turned their attentions elsewhere. The bullring was demolished in 2000 to make way for Badajoz’s Palacio de Congresos.

Executions also took place at nearby Llerena’s bullring and at the bullrings of Cádiz and Lorca. The last of these bullrings has been recently restored. Cádiz’s Asdrúbal ring was demolished in the 1970s, its use as a site for firing squads in the initial months of the Civil War reportedly having contributed to a marked decline in attendances when corridas resumed there.

1937-38

As the Nationalists gained ground, so more bullrings were brought into use to hold war prisoners - Cáceres, Plasencia, Trujillo, Gijón, Vitoria, Santander, Logroño, Castellón and El Burgo de Osma included. The bullring at Teruel - the site of a major Civil War battle - is the only plaza I’ve come across in my research where both sides in the combat used it as a prison camp as territory was won and lost. In the case of most bullrings, such use lasted only a few weeks or months, although Logroño’s Plaza de Toros de La Manzanera (closed in 2000 and subsequently demolished) held over 1,000 prisoners from 1937-39. One remnant from that time was a large map of Spain on one of the plaza’s internal walls. In 1936, the Nationalist regime ordered all of their concentration camps to put up such a map, demarcating the Nationalist and Republican territories. The aim was then to paint red and white flags on the map as the fascists’ land gains grew. An ex-prisoner of the Logroño bullring later wrote a novel in which he described the liturgy around the map, where day after day the jailers boasted about the Nationalist victories in front of their Republican prisoners.

The map at Logroño’s old bullring

The conditions

While prisoners’ time in most bullrings was short-lived (sometimes literally), the conditions in which they lived were harsh, particularly for those kept in the open.

The journalist Jaime Menéndez El Chato was one of many rounded up in the War’s final year: “Our destination came as some surprise: nothing more and nothing less than the [Alicante] bullring, where Félix Colomo, ‘el torero rojo’, had left on several occasions through the main gate. This time, we were the ones who entered through that door, and not to leave. To be fought like bulls? No, to be put to death […]

“There, on the sand, we were physically and morally exhausted, emaciated, with stained and dirty clothes after wearing them for days, even to sleep... In the centre of the arena, a score of men, most of them in uniform, although there were some civilians, proud of their large and ostentatious emblems with the yoke and arrows sewn on the left lapels of their jackets. They had come to inspect ‘their cattle’ in search of some familiar face.”

An officer commanded: “Here I want a line of officers, from captains upwards, and over there another with the political commissars!"

“Many gathered together in the two lines,” El Chato recalled, “but not all. I made a gesture to join the commissars' grouping, but a comrade, whispered in my ear, ‘Don't do it! Stay here! They don't need to know who you are. Let them find out if they want.’

“I listened to him. Even so, the commissars’ line became noticeably thinner. I immediately understood that what was a small step for many, was a big step towards their death.

“They took us to the circular corridor that surrounded the plaza, about six metres wide, with a high ceiling, an irregular floor of decomposing mortar, a lot of gravel and sand and little cement; full of braided straw chairs, with the backs nailed to long beams, to be used in boxing shows or similar. That was our new home. We were lucky, because the last selected - about 800 - were sent to the patio de caballos. A square courtyard without a roof with stables on one side, in the centre a drinking-trough, a rubbish tip, and an open toilet that consisted of holes in the ground […] a disgusting spectacle that made one vomit. About 350 found accommodation in the stables; the others remained in the damp yard, always perfumed by the toilet smells. And what about the ‘more than luxurious’ stables, without light, without ventilation?... But yes: on the floor a mixture of dry manure and straw delighted as a mattress. And with some exceptional ‘inhabitants’: thousands and thousands of spiders hanging from the ceiling, a spectacle somewhat unnoticed because of the dim light.

“The men kept arriving. Soon we ran out of space, so they were sent to the arena, whose roof was the sky […] There were about 2,000 men there, sprawled on the ground and with no possible escape from the rain. After a heavy storm, a few centimetres of water covered the ground, that enormous collective mattress that soaked to the entrails the bodies and hearts of all the comrades, huddled together without space. And yet, in the stands, there were just four guards aiming their machine guns and ready to open fire at any moment.” In these conditions, unsurprisingly, sickness amongst the prisoners increased.

As for food: “We went from a can of sardines for three people, to a can for five, to end up with a can for seven. So, curiously, by that time, there were fewer sardines in the can than there were men to share them. And the bread [40 grams per person per day] was more like a biscuit, unsalted, unleavened, and hard as a knife […]

“At night,” El Chato recorded, “we received visits from the officers, with three objectives: loot, loot and loot. And woe to him who refused to do what they wanted; death awaited […] What’s more, it was forbidden to communicate with our families. Neither did they know about us, nor did we know about them. Anguish reigned in our hearts.”

1939

It’s reckoned Alicante’s bullring saw some 18,600 prisoners pass through it in the Spring of 1939. Other bullrings used to hold prisoners in that final year of the War included those of Mérida, Tolosa, Bilbao, Pamplona, Baza, Ronda, Málaga, Guadalajara, Albacete, Hellín, Ciudad Real, Monóvar, Madrid’s Las Ventas, Valencia and Utiel. Monóvar’s bullring acted as a prison camp from April to November and saw several deaths from the cold and poor hygiene, the franquista camp inspectors eventually declaring the plaza “not fit for purpose”. Terrible conditions were also reported at Utiel, Pamplona and at Lorca, which - like the ring at Baza - also served as an execution spot.

The newspaper notice requiring former Republican soldiers to report to Valencia’s bullring and (below) the overflowing numbers of prisoners that resulted

At Valencia, the Republican Government’s headquarters for the bulk of the War, all ex-military on that side were ordered to report to the bullring once the Nationalists had taken command of the city. One of the prisoners there reckoned there were some 30,000 captives crowding the bullring at one point. Some detainees would throw pieces of paper into the adjacent street with their names written on them in attempts to tell family members where they were. People would come to the bullring to bring food or to collect bodies, for executions took place here too.

Remembering these uses now

Although Spain’s post-Franco fledgling democracy opted to try and forget the Civil War, it’s not surprising that, in recent years (backed by Government legislation) there has been a wish amongst many descendants to uncover the past as well as the thousands of bodies of combatants and civilians left in unmarked or communal graves. As part of this movement, it’s understandable that greater recognition of the sites of Spain’s concentration camps (bullrings included) has been called for.

However, at a time when bullfighting itself is a political football, care should be taken as to how this is depicted. I’ve already come across one blog posting from someone calling themselves an antitaurino effectively gloating over the Valencia plaza’s use as a prison camp. More generally, older aficionados have been smeared as being Franco nostalgists or fascists. Monuments erected recalling some bullrings’ atypical usage during and immediately after the Civil War should make it clear that they were requisitioned by the Nationalists for the purpose of imprisonment. Prior to that, of course, the majority of these rings were in the hands of Republican authorities; failure to refer to their requisitioning can leave the false impression that these bullrings were aligned with the franquista movement.