Modernising bullfighting’s implements

In mid-2019, I wrote an article for the Club Taurino of London’s magazine La Divisa on the winning essay in the 2018 Doctor Zumiel literary taurine competition, whose topic had been ‘How should the lidia be adapted for the 21st century?’ The essay had been co-written by Fernando Gil Cabrera (who was also a co-author of an important 2007 study into the bull’s experience of stress and pain during the lidia) and Julio Fernández Sanz.

Now, Fernández Sanz has written a book, Descubriendo al toro de lidia, which again puts the case for modernising the corrida, with a particular focus on making changes to some of the implements the festejo involves.

Fernández Sanz is a veterinarian and former Technical Director of the UCTL’s Libro Genealógico and previously headed the Union’s Departamento de Investigación Veterinaria, specialising in work on DNA and genetics. For the past seven years, he has been working with former matadors José Miguel Arroyo Joselito and Manuel Sales and the apoderado Enrique Martín Arranz on making improvements to bullfighting implements.

Although sub-titled ‘An audit of the bullfight through its tools’, the book is much more than this. It’s a 311-page large format paperback with a lot of illustrations and covers the auroch, considered to be the wild ancestor of today’s cattle; the domestication of cattle and the early migrations; the bull in the Iberian peninsular; the creation of the fighting bull, what Sñr. Fernández calls ‘la raza bovina de lidia’, and how the animal differs from other cattle; taurine-related activities that predated the bullfight; the corrida de toros; erroneous myths that have hindered bullfighting’s development; and implements for the lidia and how they can be improved. It is these last two topics that most relate to that prize-winning Doctor Zumiel essay of four years ago.

It is important, though, to understand the context in which Fernández Sanz is writing. His view is that, in much the same way as the peto was introduced in the early 20th century to take account of changing sensibilities about the use of horses in the bullring, so, with the growing influence on public opinion of Anglo-Saxon/North American culture in the 21st century and its attitudes towards animals and death, it is time for the corrida to improve its image by moving away from some of its traditional elements.

Fernández Sanz highlights three myths (all connected with the suerte de varas) which no longer need to play a part in the thinking behind bullfights:

The bull needs to be bled in order to avoid the animal becoming congested and unable to perform later in the lidia.

The muscular damage inflicted by the puyazo helps the bull lower its head in the faena.

Piccing also slows the bull’s charges.

Through explanation, photos and diagrams, Fernández Sanz shows that the first of these myths is linked to what, in Spain, was thought to be the cause of most human deaths in the 18th and 19th centuries. These days, a heavily-picced bull will lose some 7.5% of its blood (compared to the 9% of their blood which humans regular donate), but blood-letting as a restorative has been thoroughly discredited by modern medicine, and tientas, in which blood loss is minimal, have shown no decline in animals’ performance occurring as a consequence. The cutting of the bull’s skin, however, does play its part in promoting stress and the release of neurohormones that increase the animal’s energy reserves and take away a focus on pain. The second myth is disproved because most puyazos are aimed at la cruz, an area behind the morrillo where there are no muscles affecting the bull’s head: if piccing took place in the morrillo (where muscles that lift the head are based), Fernández Sanz argues only half the objective of lowering the animal’s head would be achieved, as the muscles used to lower the head are actually situated beneath the bull’s spine and in its lower chest. His view is that a bull’s ability to humillar is more a product of its selective breeding. Finally, the slowing of an animal en varas is more a result of the bull’s collision with the peto and its attempts to overturn horse and rider than any piccing it receives.

(l to r) The puya used in Andalucia, Castilla y León; the puya used in the rest of Spain (other than the País Vasco); and the proposed new puya.

Taking these points into account, Fernández Sanz and Manuel Sales propose a much-reduced puya (see the illustration above) with a quadrangular-shaped blade rather than the current pyramid structure as this produces a cleaner, single-trajectory wound and, they say, by retaining this shape down to the crosspiece (the corded tope being done away with), makes impossible the action of barrenando - driving in the puya to further enlarge and deepen the wound. The reductions in the puya’s size and the damage it causes would also permit a return to a suerte de varas in which the bull charges in to the horse more than once, increasing the aficionado’s enjoyment of the spectacle and his/her ability to judge the bull’s quality.

One other change is proposed to the suerte de varas and that is having the guard on the picador’s right stirrup constructed of kevlar or nylon instead of the metal implement currently used, as heavy impact with the latter has been shown on occasions to fracture bulls’ skulls.

Indeed, the wellbeing of the bull and the toreros is a major theme running through a number of other suggested changes. Manuel Sales has already invented banderillas that flop down onto the bull’s back and sides rather than stand proud, risking injuries to toreros’ faces and eyes. Similar thinking about avoiding injury is now being applied to the divisa and further suggested changes to the banderillas. The Reglamentos currently mandate a two-winged barb for the divisa, whilst banderillas involve a single-barbed hook. A poorly-placed divisa can incapacitate a bull for the lidia, while its hooks - like the banderillas’ - can injure toreros, particularly during the suerte de matar. Instead, it is proposed to use for the divisa a narrower, single-pointed punzón inserted in a piece of PVC, which remains above the wound, and a similar fitting for banderillas (see below).

The proposed new divisa implement (top) compared with the existing

The proposed new banderilla barb compared with (top) the one used today

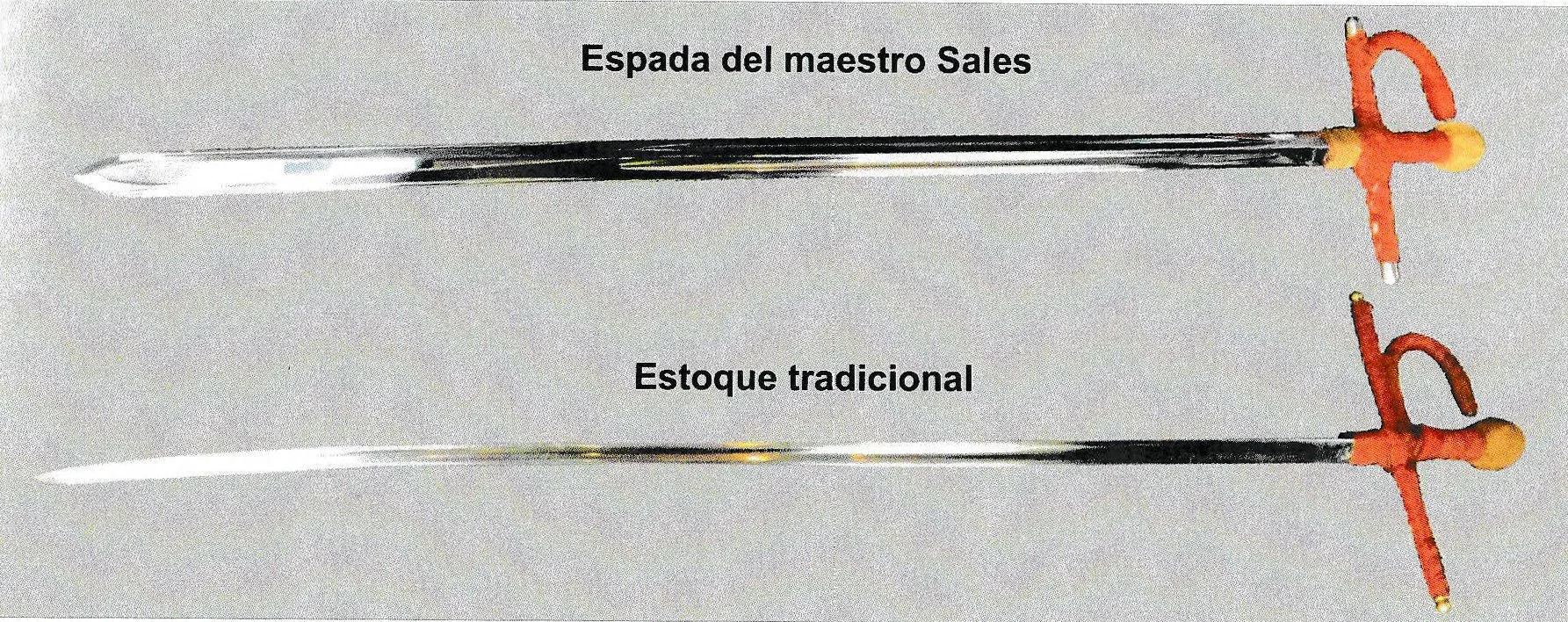

The other main innovation involves the killing sword. The present regulations require that the espada be made of steel with a maximum length of 88cm from hilt to sword-tip. Modern estoques curve downwards slightly as they near their tip, helping prevent a too-flat swordthrust trajectory. The implement is essentially lethal because of its cutting ability, yet mozos de espada tend to sharpen sword blades only for the first 10-20cm from the sword tip and a curved blade is less effective at cutting than one that is straight. Furthermore, repeated filing of a blade reduces its cutting ability. A more effective sword, proposed by Manuel Sales, features a straight and broader blade, its edges sharpened to within 20cms of the hilt, and ending in a triangular or rhomboid tip as this has been found to be better able to cope with hitting bone, adjusting its trajectory and finding a way past the obstruction rather than getting stuck. Tests have shown that Sales’ swords, which accord with the regulations, invariably lead to a rapid death of the bull without the need for a descabello. Fernández Sanz argues that a reduction in the time taken to kill a bull “favours success for the matador and for the spectacle as a whole,” quicker deaths assisting the matador to win trophies as well as being less concerning to modern sensibilities.

The problem with these suggestions (apart from that of the estoque) is that they require changes in the Reglamentos to become the norm and no major political party (apart from Podemos, whose approach would not be helpful) is likely to want to tackle a change in bullfight regulations at this point in time. However, there is one exception to this straitjacket - the corrida concurso, in which departures from the norm can be permitted. July 23 this year will see the return of Jerez’s corrida concurso, and the festejo will feature the use of Sales’ implements, a condition put forward by one of the participants, Morante de la Puebla.

(Thanks to Herbert Wiese for his assistance with this article.)