La Magdalena 2024 (Part I): An aperitivo of four mixed dishes

Jock Richardson

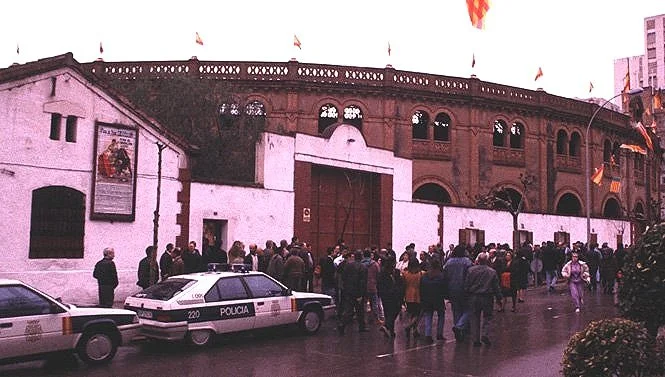

Sunday, 3 March: Not the usual victorinada

Last spring, we saw Paco Ureña and Emilio de Justo in an epic mano a mano victorinada in La Corrida de la Prensa in Madrid. How different was the corrida today – five victorinos and a valdefresno for Paco Ramos and Borja Jiménez mano a mano. Overall, the victorinos tended to weakness in their legs, were very short in their charges, turned quickly and tended to raise their heads defensively at the end of the lances and pases. They lacked the aggression so typical of the hierro and so stimulating of emotion.

Paco Ramos is from the region of Castellón and is much beloved by his compatriots. He took the alternativa there in 2005 and has had relatively few corridas since. He usually appears in la Magdalena and, no doubt, takes on whatever bulls are offered to him. He is not bereft of technique and overflows with courage and good intent. On the evidence of today, that matters little when he demonstrates his ineptitude at the kill. He heard an aviso in his first and took three descabellos to kill; with his second, he took nine descabellos after an aviso; with his third victorino, he needed six entries with sword. And so, all his efforts, his courage and his technique turned to dust.

His first animal was on the borders of being a novillo for its appearance; it had an unimpressive size, a poor head and soon proved that it was slow, halt, and dangerous, raising its head after rapid turns. For a brief phase, Ramos brought it under control with low derechazos and then took it through mid-height derechazos and naturales, with huge remates sending the bull well off and giving himself distance for the next pases. This was impressive work, but the bull soon slowed down and forced Ramos’s sheer persistence and desire to please into a long session of pase pegging that only conveyed a feeling of danger, impending doom, and the descent into the eventual defective kill.

Paco Ramos (image from Plaza1)

Ramos’s second was much closer in appearance to what is expected of a victorino, but it was insipid in its slow-walking docility. Ramos can find the correct cite positions and he has a positive and natural grace when his toreo is allowed to flow. And so it did, in fits and starts, with this characterless bull. So well-structured and composed were his best series of derechazos and naturales that his compatriots may well have given him an award. All chance of that disappeared in the defective sword thrusts and the battalion of descabellos.

The fifth victorino really looked the part in its past middle-aged solidity. Perhaps it was that and the wind that had blown in gusts all afternoon that led to Ramos’s confusion. The bull was heavy, lumbering and lacking in the energy to turn its obvious nobility into charges. Paco Ramos tried, and he tried hard, to make it engage with his single pegged pases, but it was what it was - a long and tedious exercise in trying to please. The final incompetence of the kill ended a sad afternoon for the matador.

Borja Jiménez is from Espartinas and the technically skilful aspects of his toreo remind me of Espartaco to the extent that I wonder if the toreo of the latter has had a strong influence on the former. The lad is certainly confident, sure of himself and dedicated to demonstrating his powers almost to the extent of flamboyance. The weakness of today’s victorinos has been mentioned. The second fell over several times, threw a front foot forward in an invalid way and was soon returned to los corrales. The only substitute listed was a Fraile Atanasio/Lisardo Sánchez pupil from Valdefresno. And a fine example of its breed it was. Huge in appearance, with magnificent trapío and a willingness to charge nobly that was an unexpected gift for an enthusiastic matador. The welcome of close, erect, florid chicuelinas and a revolera signalled what was to come: the unfolding of a lidia by a man and bull in close harmony. The bull engaged bravely with the horses and charged well to the banderilleros. As the faena unfolded in orthodox pases and a molinete that did not quite work, it became obvious that here we had a torero well-endowed with technique but lacking in those virtues which, applied to a bull of this nature, allow the creation of taurine art: style and grace. For this aficionado who believes that all art must have technique as fundament this is not a problem. It took the great – dare I say that – Espartaco years to marry grace and style with technique just as many others did. Given sufficient opportunity of the right kind, Borja Jiménez will rise to the summit. By the end of this faena, he was working in tight terrains with cambiados and luquesinas to appreciative applause. Having killed with an estocada tendida of fulminant effect, his ear was justified.

Borja Jiménez (image from Plaza1)

The fourth bull was another fast-moving quick-turner and Jiménez soon had it under a measure of control. It passed through the first two suertes with flying colours. It may be that that encouraged him to dedicate to El Soro, seated in regal splendour on la meseta de los toriles. Such an honour deserved the now customary trumpet treat of El Soro sounding a fanfare. It is pure circus sentiment, but it is hell of a good fun. The weak and ambulatory nature of the bull condemned Borja Jiménez to the pegging of single pases. That he does rather well, but in his genuine effort to please the crowd with his long-winded arrimón, he lost all connection with them. He ended with an estocada off a curve.

The sixth bull was another well presented victorino which tended to charge wildly at first but soon slowed down to charge in short bursts. Its condition was ideal for Borja Jiménez’s close range toreo, pulling the bull closely round in tight circles. This kind of toreo is an acquired taste and most of the public here today had acquired it. The delirious favour for the torero increased with the ever tightening of his toreo and when he killed promptly with an estocada, he had won another ear, a triumph, and a main gate.

Lyn Sherwood, that taurine critic who wrote in San Diego newspapers, used to explain to us all in one of the taurine chatrooms that Castellón was the most exigent plaza in the world. He had found that out as his ship lay at the roads outside the port way back in the 1940s. He would be turning in his grave at the triumphalism of Jiménez’s second ear and main gate today.

Monday, 4 March: Heaven for horse fans

It may seem hypocritical for a man who has spent sixty years decrying the exercise of rejoneo to write a report about it. When people ask me why I bother to go, I reply, as Rafael El Gallo used to do, by saying that there is nothing else to do in Spain between cinco y ocho de la tarde. I add that one has no right to criticise something that they have neither seen nor studied and that attendance gives me an opportunity to watch murubes. I’ve studied it as far as the books and its devotees have been able to teach me. I am quite proud that I once went to the University Library of San Luis de Potosí for no other purpose than to buy a book they had published on the subject. It was closed, so I had to buy a second-hand copy in an ancient bookshop nearby. So here is my first ever horse boy report.

The cartel for the day was of murubes from Fermín Bohórquez for Andy Cartagena, Diego Ventura and Lea Vicens. They have, as have all rejoneadors, been overcast for years by the dark shadow of Pablo Hermosa de Mendoza; it seemed that nobody could topple him from the summit of his consummate successes. But he is going now, and they must compete with the man who has been making fireworks under the cloud for years – Diego Ventura. In my opinion, this cartel demonstrated three styles of rejoneo; it certainly did today.

Andy Cartagena

Andy Cartagena is a consummate professional who tends towards the flamboyant, peppering his performances with demonstrations of horsemanship miles away from and entirely irrelevant to the bull: marches across the ring by a horse – and these are huge horses – walking on its back legs; standing on the barrera waving his weapons and milking the crowd; presenting his ‘Humano’ with its flowing mane and tail like the mount of a 16th century emperor. He took a while to reach harmony with his first ordinary but not illidiable toro, placing his first rejón off a cuarteo with the horns way past the stirrups. The second was placed on top off another cuarteo. After another cuarteo for his first pair of banderillas, he was citing de frente and placing accurately with the horns at the stirrups. This was great: he marred it by missing with two out of his four cortas. One of the most interesting elements of rejoneo, as I see it, is the ease with which the bulls’ querencias become obvious and the skill, or lack of it, with which the rejoneadores extract the animals from them. This bull dug in against the boards opposite the toriles: Cartagena challenged it, made it move, and rode it to los medios in a silken manoeuvre. And that was that: a rejón in the correct place and a descabello ended a relatively unconvincing performance.

The fourth bull had much more character than the first and Cartagena used its willingness to place three rejones de castigo from cuarteos each with the horns at the stirrups and each precisely placed on top: calm, beautifully thought out and executed – a great start. He rode across to los toriles, removed his hat and ceremoniously dedicated – I presume that is what he was doing – the death of the bull to the immaculately dressed trumpeting archangel of the Levant – Vicente Ruiz El Soro. It seems awfully pre-arranged to me, but as El Soro took his instrument from wherever he keeps it, not even I could criticise it. The trumpet solo was one of the brightest events of the afternoon. What followed was not bad either. The placement of the banderillas from frontal cites to neat quiebros were precise and convincing, even though marred, for me, by the tight pirouettes after the placements. The skill with which, the mane and tail of ‘Humano’ contributing to the huge sweep of the manoeuvre, Cartagena drew the bull out of a querencia opposite the President was uplifting. And then, the bull now exhausted and unable to charge, he took four attempts to kill and lost all for which he had striven so nobly.

Diego Ventura

Diego Ventura has been setting out his stall for years. He did not cut the tail in Madrid a couple of years ago for nothing and he has had great successes elsewhere. Now, he is no longer the spare! To start with his first bull, he took the difficult route three times, approaching from the front, executing tight, late, quiebros close to the horns and still managing to place the rejones at the stirrup with perfect precision. The way he moves the bull from place to place with breathtakingly smooth temple, especially when in tight terrain against the boards, is wonderful also. Only once, when a banderilla fell out in the lidia after a placement between the stirrup and la grupa, was there a slight fall from grace. Every banderilla was placed from a frontal cite – once he mistimed the approach, stopped the horse for a second to reach harmony with the bull again before proceeding. Finally, unfortunately with less ceremony than he had done in the tail performance in Madrid, he removed the bit, bridle and reins from the horse and took it naked to place a pair of banderillas immaculately. Ventura had kept his horses under control throughout; he had made his cites de frente; he had placed his weapons accurately, even from close to the bull. After a spectacular kill with a fulminant rejón, he had achieved a near perfect performance. He had assured two ears and the Main Gate.

The fifth bull was a much less cooperative one than had been the second: it was unfocussed, moved more and more slowly and tended to take up querencias. Ventura tried to teach it to lengthen its charges, largely by templando it for long distances along the boards, the horns close to the horse’s side. I can’t remember whether that manoeuvre is called a hermosina, a mendocina, a pablocina, or some other name from the Estellan dictionary of rejoneo; answers on a comment please. Ventura does it very well. The whole faena was an exercise in tight rejoneo carried out in a small space, Ventura managing to place his banderillas accurately and to keep the bull focussed. It was workmanlike rather than inventive and began to drag a little as it unfolded. Ventura brought us back to life with another of his fulminant kills and retained his reputation as a great rejoneador.

Lea Vicens (image from sol-y-sombra.fr)

If Cartagena is a flamboyant showman and Ventura is an encyclopaedic technician and artist, Lea Vicens comes somewhere between, perhaps leaning a little too far to the showy manoeuvre, the look-at-me gesture and the clever tricks of horsemanship. Today, she had a good day. She started with her first in as much galloping as seen in the Cheltenham Gold Cup, often avoiding the seeding of peones that seemed to get everywhere in the ring. That said, she did place two rejones from cuarteos in the right places. She tends to eschew the more difficult frontal approach, so all her banderillas save one pair were placed from cuarteo. All, including the frontal pair were commendably accurate. In fact, we were watching a competent and compact piece of work to a strong bull by a rejoneadora with all her papers intact. Her rejón de muerte fell slightly crosswise, but there was no denying that she had earned an ear.

For me, her work with the sixth bull weighed horsemanship heavily in the balance against the “art” of rejoneo. It seemed to me that Lea was intent on running the bull to exhaustion rather than bringing it to its death by calculated use of rejones and banderillas. In her favour, it must be admitted that she did embed her regulation set of weapons in accurate cuarteos and that the horsemanship was convincing. There was a good deal of transportation of bull around the ring templando its charges cleverly. To me, the pirouettes after placement were all circus, performed far from the bull: they were delicious spectacle to most of those present. A second successful kill gave her another ear and a share in the triumphal exit on shoulders from the plaza.

Tuesday, 5 March & Wednesday, 6 March: The interesting game of the novilladas sin pics

In the Bar Garrofera in Algemesí, home of a great novillada feria, hang several carteles from the middle of the 20th century. They are of the ferias that took place just before we started to travel to Spain. Thirty or forty names appear on each one, perhaps 120 in all. Of the ones we saw as matadors in the early days of our afición, only three appeared on these carteles. The rest must have fallen into decay like dead leaves at the side of the upward climbing roadway to taurine success. I imagine that the same could be said of everywhere else that encourages lads in their early days and that bars in Arnedo, Morarzarzal, Villaseca de la Sagra, and up the Valley of el Tietar tell similar stories. On two days we have had novilladas without picadors here in Castellón. As we left the plaza tonight, 6 March, we met an old friend to compare notes. “How far do you think Olga Casado will go?” was his opening remark. The truth is that we cannot at this moment tell. So much depends on the teachers in the taurine schools; the taurinos, families and friends who put their faith and support into youngsters; the capacity of those budding toreros to learn and develop; and luck. It is always a guessing game for we devotees of the novilladas sin picadores events. I admit to being a poor player of this guessing game. My rules for guessing were laid down when we saw Joselito, El Fundi, El Bote, Antonio Carretero, El Juli, Antonio Ferrera, Rafaelillo and Sebastién Castella making their first steps in Bayonne, Mont de Marsan, Madrid, and Dax. In the cases of Ferrera and El Juli, they were the first days that they had ever worn trajes de luces. All of them performed varied and mature toreo and we knew they would all make the grade. Things are not so certain this March in Castellón. I invite you to play the game by keeping your eyes open for the careers of the ones we have just seen: Fran Fernando (Murcia), Javier Aparicio (Castellón), Pablo Vedrí (Castellón), Abel Rodríguez (Castellón), Bruno Giméno (Valencia), Jorge Hurtado (Badajoz), Arturo Cartagena (Onda), Daniel Antazos (Valencia), Bruno Martínez (Castellón), José Almagro (Castellón), Nicolas Cortijo (Albacete), Olga Casado (Madrid) and Ian Bermejo (Castellón).

A feature of these events is that the actors have been carefully taught. It seems to me that the curriculum is the teaching of the execution of lances and pases that will show off what the pupils of the schools have learned. Unfortunately, that process is not designed to instil the knowledge and ability that will allow the neophyte to launch him or herself over the horns of a calf that they have prepared for the kill. Indeed, so keen are the youngsters to give passes that they far too frequently go on and on trying to pass an ever more exhausted animal. When it comes to the kill, all confidence has seeped away from the torero, all strength has seeped away from the eral and the finale is a plethora of avisos, pinchazos and descabellos. So was it for many during the two March days in Castellón.

Fran Fernando (image from novillero’s X.com page)

The tall Fran Fernando showed several virtues. He positions himself well in the cites, runs the hand well in templados passes, but went on for too long and lost the attention of his initially noble Sepúlveda (all in the first novillada were from this atanasio herd). He killed well with an estocada and a single descabello and did not disappoint.

Javier Aparicio has a long way to go. His cape and muleta were repeatedly caught, he maintained a huge linear distance between him and the docile, beautifully endowed with atanasio accidentals, novillo. He gave us the first manoletinas, which seem to be compulsory in these events, and, having exhausted his calf and run out of ideas and time, killed in a cloud of pinchazos after the aviso.

Pablo Vedrí (image from novillero’s X.com page)

Pablo Vedrí, short, confident, and green suited, had already performed a breath-stopping quite of high delantales and a verónica to Aparicio’s novillo. His sepúlveda was an erratic runner at first and he took a while to engage it in some wild but enthusiastic verónicas of gradually increasing control. At last, we had a torero toreando. There was a degree of control also in his opening series of seven derechazos and the positive collection of right-handed pases that followed them. There were lots of sparkling moments after he had decided that what we should have was a demonstration of pase pegging from one of those books describing pases. They were not as described in the books, but his distant orthodox pases, his explosive molinetes, his positive naturales, did evince a deal of confidence and goodwill and the germs of a taurine ability. He went on beyond the second aviso and killed with an estocada and a descabello.

Abel Rodríguez is another pupil of the Castellón school, which, judging from the huge mass of hankie-waving teenagers in the upper tendido, must be bulging at the seams. Maybe that is why they all get the same lesson: “Give ’em lots of pases and don’t forget the manoletinas!” Abel had performed a ropey but exciting quite of chicuelinas to Vedrí’s calf and had my compañera shouting, “No! No! No!” as he wended his erratic way to la portagayola. He was fortunate that the bull was focussed and the larga was a success. At least, Rodríguez gave us the menu in a tall, erect, style until he started to stick his trunk into the flank of the bull after it had passed at the discreet distance dictated by his outstretched muleta. Then he was severally bumped in an undignified fashion. After his curate’s egg of a faena, he placed an estocada atravesada and to the music of the avisos given over six minutes to dispatch the bull.

Bruno Giméno (image from Ateneo Mercantil)

Bruno Giméno had performed an impressive quite of elegant upright chicuelinas, gaoneras, and afarolados to the fourth novillo, so it was no surprise to see this self-confident lad striding to the gate of fear to place himself in what the man in front of me called “Mucho, mucho, compromiso”. It all came off admirably, but Bruno lost his cape in the set of pedestrian lances that followed. It is awfully easy to be excited by the flamboyant work of a master showman. He is, though, more convincing when he approaches his toreo seriously. He cited well from the exact distance several times, rested the bull well and performed some beautifully templados pases. He eventually entered to kill and paced the sword into the novillo’s ribs. In a moment of sheer magic, he withdrew the sword and placed an effective estocada. The pandemonium that ensued ended with the award of two ears. Later in the evening, I was toying with my phone in our Gin and Tonic bar trying to identify who the young men at the adjacent tables were. They were toreros, but they always look different without the Brylcream and the flashy suits. Giméno is no Johnnie come lately. He has won competitions up and down the Levant, won much praise and has a mano a mano contract in Bocairent in May with the novillero whose career is being blessed and forwarded by none other than John the Baptist: Marco Pérez.

Jorge Hurtado was tentative and insecure to start. No wonder, the novillo was unfocussed and difficult to engage. Hurtado showed his good manners as he tried hard to bring the weak and wandering eral to heel and he did manage to get sporadic derechazos templados and some afarolados at the end.

The novillos for the second day were from the ganadería of Hermanas Angoso Clavijo, an Asociación herd of Garcia Jiménez, that is of Juan Pedro descent. Arturo Cartagena took several minutes to engage with his distracted novillo. How hard he tried, and how little he gained from his efforts. The novillo was reluctant, but when he did get near it, something he avoided carefully, he or his lure got caught. There were complete single pases performed with more caution than merit. His estocada was brilliant, but he has not passed third grade yet.

Daniel Antazos drew a strong and focussed eral and performed highly competent and visually satisfying opening verónicas to it. His faena was a mixed bag of single pegged pases of varied types and complete and often templados series. Had he imparted some structure and a narrative line, it would have had real merit. As it was, he indicated a good deal of promise and, had he not required two sword thrusts, his vuelta might have been completed with an ear in his hand.

Bruno Martínez is yet another pupil of the Castellón school of toreo. This lad remembered what he had been taught there and made a conscientious stab at creating the Castellón school faena. In the middle, there were meritorious series of linked pases with each hand and had he not repeatedly drawn the novillo in towards him to be caught, the whole thing might have been nicely rounded. I felt for him and so would other prácticos amongst you who have done the same thing again and again with these little bullet cows the taurinos charge you a fortune to torear. Bruno’s opportunity ended as he placed an estocada so crosswise it exited the novillo’s side.

José Almagro, another Castellón hopeful, started off exceptionally well with cape and muleta to an extremely cooperative animal. He was building hope for the aficionado and success for himself as he went on creating a well-structured faena. Then suddenly, he went feral and started to do what the Cordobés family did rather well – frog jumps after the novillo had passed. He was soon flying through the air and confusedly placing ineffective sword thrusts and descabellos.

Nicolas Cortijo is a tall youth and, as he performed his opening larga cambiada de rodillas and verónicas in a vertical and elegant style, he reminded me of Manuel Caballero. He has a varied repertoire with the muleta and, except when he allows enganches, conveys a feeling of competence. In the end, he sinned the sin of all novilleros sin pics: he went on and on with an unnecessary and ragged arrimón. It took him a pinchazo, a vertical media and an aviso to dispatch his eral.

Olga Casado (image from Cope Ronda)

Things were not pointing to a rosy future as the twelfth novillo appeared. It was back to some serious work for most of the students we had seen. But “Cometh the hour cometh the woman” in the shape of Olga Casado. I was quite ashamed when, in a later evening discussion, having said that I had never seen her before, had it pointed out that she had appeared in this, that, and the other, televised sin pics event that I had definitely seen. I will not forget her again. From the assured good-mannered verónicas of her opening to the border between her final brilliantly executed series of naturales and the, apparently compulsory, tight, and unnecessary arrimón with which she ended, she gave as near to a completely artistic faena as one has a right to expect from a relative beginner. Built on series of naturales en redondo, she was in complete control of self, novillo and the public as she created a compact faena of long, templados, pases with each hand. She performed toreo with grace, intelligence, and skill. She killed with two pinchazos off curved entries. Her work had not been perfect, but it had been very convincing indeed.

Ian Bermejo had a hard act to follow. He walked to the portagayola position and awaited his eral on foot. The gaoneras to welcome were rough, but his subsequent afarolado, largas cambiadas de rodillas, verónicas chicuelinas and a recorte were enthusiastic and full of conviction. The novillo was weak and exhausted by now. That did not prevent Ian from pouring out a multitude of derechazos, some of them invertidos, at a huge distance from the eral. As he made a semblance of defying the stationary and rajado calf in tight pases and epic desplantes, he looked quite satisfied with himself.

As we are at the beginning of a season watching taurine careers being launched, it is impossible to say which of the 17 school pupils seen in Castellón will get to the alternativa. Many of them will appear on CMM, Telemadrid and Canal Sur – maybe even on OneToro TV. I will be watching to see how they develop.