El Niño as ganadero

His bulls’ usual fare: El Niño de la Capea with Pablo Hermoso de Mendoza before a corrida de rejones

In my book Dialogues with Death, the matador Pedro Gutiérrez Moya El Niño de la Capea discusses his breeding of toros bravos. “I bought Carlos Urquijo’s murubes more as a good business deal than because I knew what the ganadería really contained,” he says. “The best of them surprised me a lot, because they had a way of charging I didn’t see in the ganaderías I was used to appearing with, like the atanasios or bulls from Arranz, Núñez or Domecq.”

He then went on to develop the herd as he saw fit. “To begin with, I concentrated on settling their comportment - always en bravo. There are various characteristics which favour fierceness and induce particular comportment, for example, large lung capacity - a sufficient chest, as with an athlete, to oxygenate in a matter of seconds so that refreshing of the blood enables the animal to keep on charging.

“Another characteristic that distinguishes my bulls from others is the hindquarters. If one of the qualitative differences of murubes is their gallop, the initial impulse to accelerate forward has to come from the back legs. They must be vertical, straight and sufficiently strong for this impulse to get a mass of 600 kilos moving. And they have to lift their hooves up to their body to attain the continuous rhythm of the gallop.

“I want a bull that’s disposed to attack, that wants to come forward and is never on the defensive. For this to happen, the animal needs to be big-chested with forward-pointing horns, as this gives it security and confidence when charging. It also needs a straight spine to attack with its head down rather than up… It should also have short legs, lowering its centre of gravity, for, with long-legged bulls, the turns they must make require greater effort and bring on lethargy. If a bull has no desire to attack honestly, the emotion of art, which is so highly prized by the public, cannot exist.”

Two decades later, Pedro has recently informed Pamplona’s Club Taurino in a colloquio that his herd should no longer be considered as murubes. “Over time, I learned that genetics, selection and management are the three pillars to being a good ganadero. I dare say that my breed is no longer Murube: it is mine, because it has many generations of cows kept under the same criteria, without influence from any other livestock in the area.” A distinct encaste has to be recognised by la Real Unión de Criadores de Toros de Lidia (RUCTL). To be awarded this status, a ganadería should have a history of 30 consecutive years of breeding without the introduction of another bloodline to the herd; a defined morphological appearance to the adult animals, both male and female; and a selection orientated at achieving determined characteristics of comportment.

“You have to invest a lot of money,” says Pedro, “because not everything that is born on a ranch is suitable for a corrida; not everything has to be taken to a corrida - only those animals you think are going to perform well. If you make a mistake, you are wrong. If you get it right, you get it right. You have to have in your head that bull that you would have liked to torear. And, for this, you have to do a lot of tests.”

El Niño has now divided his bulls into three herds - El Capea (formerly known as Pedro y Verónica Gutiérrez and San Mateo), which is registered with the RUCTL, and two (Carmen Lorenzo Carrasco and San Pelayo) that are registered with la Asociación de Ganaderías de Lidia (AGL).

As someone who once said that matador-ganaderos have an advantage over other ganaderos in knowing what to look for in a toro bravo, it must be somewhat frustrating for Pedro that, whilst profitable, all three of his hierros are commonly seen in corridas de rejones and comparatively rarely in corridas de toreo a pie. The bulls are good-looking, but often are modestly horned, which makes them more suited to rejoneo, while the animals’ tendency to have short necks can also prove problematic for toreros on foot.

Last year, in addition to several corridas de rejones, El Capea bulls took part in just two full corridas of foot toreo and three corridas mixtas. At Guijuelo, they yielded six ears to El Fandi, Manzanares and Diosleguarde, while at Villanueva del Arzobispo, the bull ‘Jicarón’ was indultado by Alejandro Talavante (the matador stupidly tried to lead the bull into the toril at the faena’s end and was injured as a result) and a faena from Curro Díaz won two ears. Enrique Ponce also cut two ears from an El Capea bull in a corrida mixta during Salamanca’s feria. To date this year, four bulls of Carmen Lorenzo Carrasco have been fought at Valdemorillo (in a corrida mixta in which Diego Ventura faced bulls of El Capea), Sebastián Castella cutting three ears. With these kind of successes, perhaps El Niño’s bulls will become more frequent participants in corridas de toreo a pie.

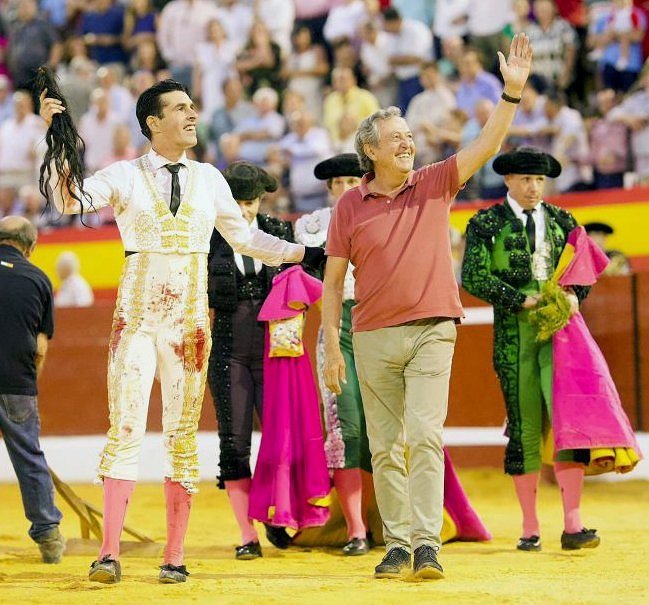

El Niño de la Capea, acknowledging the crowd’s applause after the indulto of ‘Jicarón’ (image from chicuelinasytafalleras.com)